Amsterdam Real Housing Prices Highest in 400 Years. An Analysis of a Bubble.

Housing prices in Amsterdam, corrected for inflation, have never been this high since recorded history. Next to low interest rates, the cause of rapidly rising prices is a feedback cycle between banks and consumers having become addicted to mortgage lending and ever-increasing prices.

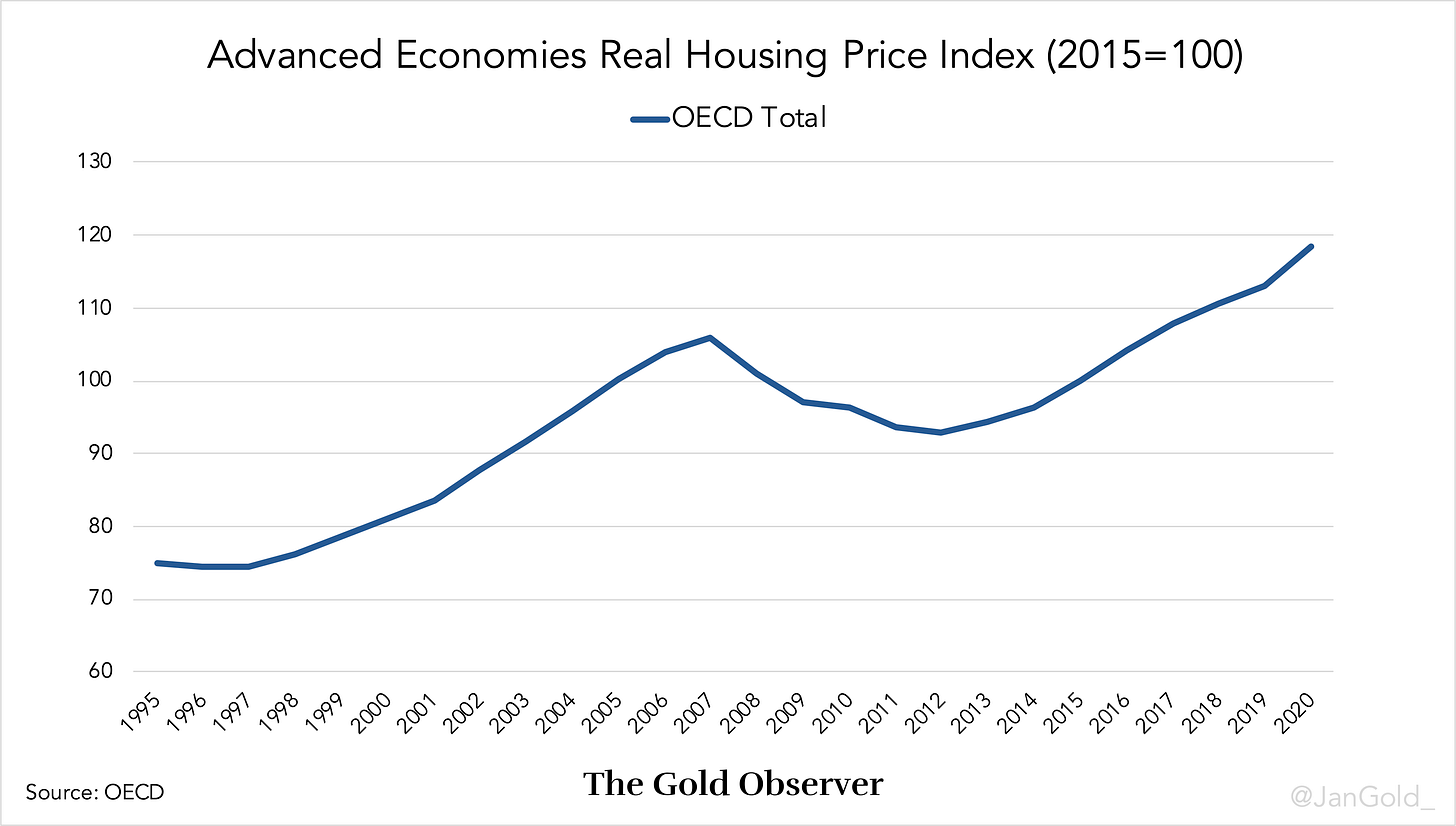

With the Great Financial Crisis—caused by a real estate bubble—still fresh in our memories, in many advanced economies housing prices are currently rising at a record pace. In the Netherlands housing prices were up 19% in the third quarter of 2021, compared to the year before.

Some economists perceive housing prices in Amsterdam—of which I have obtained the longest-running index—to be overvalued since 2020, based on a model of rent prices and interest rates. Others point towards policies implemented in the West over many decades that have created a “housing-finance feedback cycle,” wherein banks have become addicted to mortgage lending, fueling housing prices, and consumption increasingly relies on the “wealth” generated by rising prices. Because this trend makes banks lend less credit to productive businesses, the very core of economies is weakened.

The Longest-Running Real Estate Index

Several building blocks of capitalism have been invented in Amsterdam, the capital of the Netherlands (Holland). In the late 16th century, the Dutch embarked on trading expeditions over sea to Asia. By 1600 there were six fledgling “East India” companies sailing from Dutch ports. To combat Spanish and Portuguese competition, and not compete against each other, the six existing companies merged into one: the United East India Company (De Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC for short). The VOC was formally chartered in 1602, and became the first joint-stock company, with its shares changing hands on the first stock exchange. Money from all over Europe poured into the Netherlands. Because of the VOC’s extraordinary success Amsterdam needed to expand, and did so by digging three canals around the medieval city center: the Herengracht, Keizersgracht, and Prinsengracht.

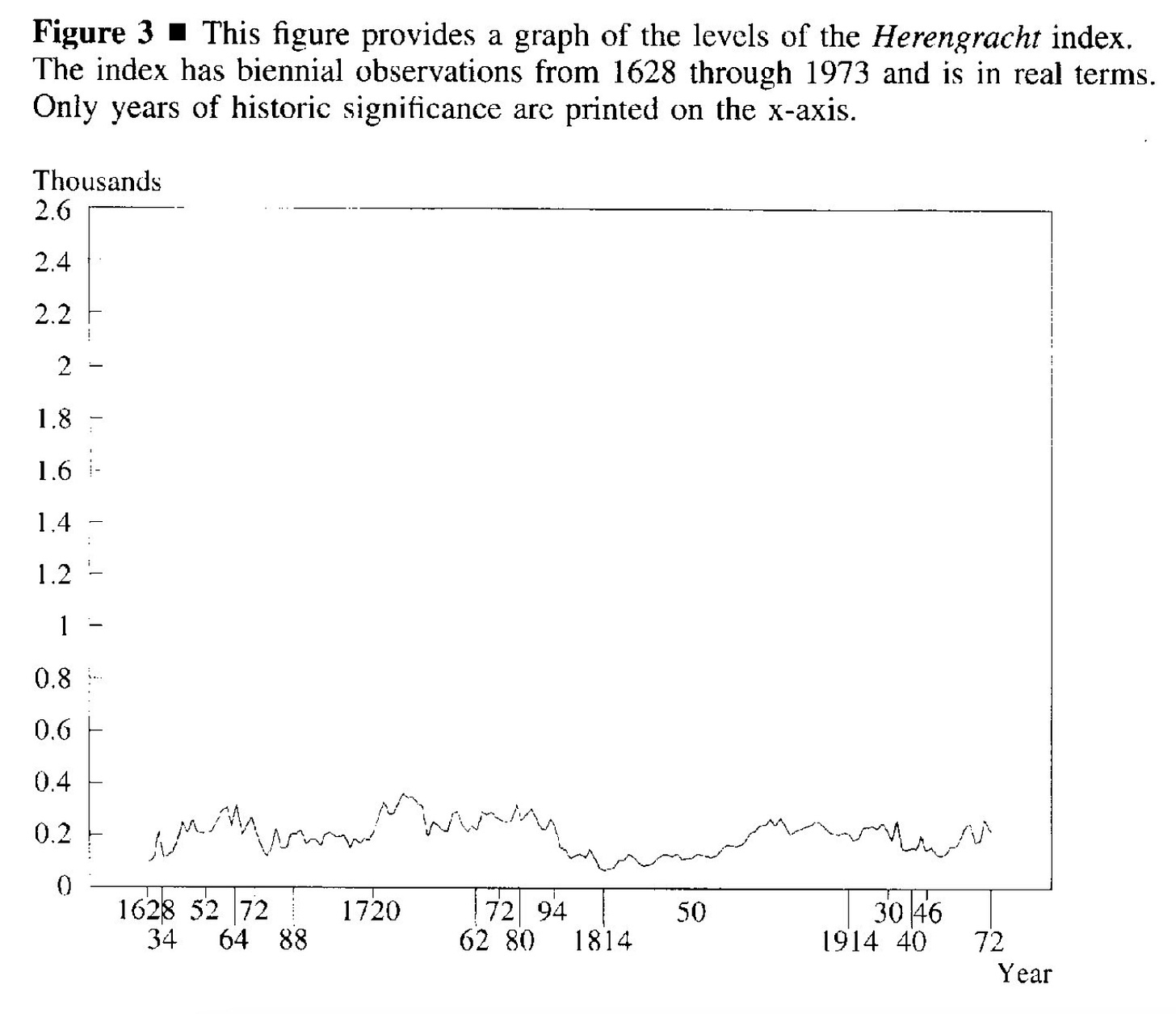

Transaction prices of real estate on the Herengracht, the finest of them all, have been carefully recorded. In 1997 Dutch economist Piet Eichholtz build a price index of houses on the Herengracht with a constant quality from 1628 until 1973. This was the birth of the Herengracht Index. Eichholtz’s initial research showed that real housing prices (corrected for consumer price inflation) gradually changed over time, but were fairly equal in 1973 compared to prices in 1628.

Eichholtz et al published an update on historic housing prices in Amsterdam in 2020. For this publication Eichholtz et al collected a deeper set of data, which starts in 1620 and includes houses from a wider area. Although the numbers show prices started to rise significantly from the 1990s onwards, their conclusion was that the housing market was not in a bubble, based on rent prices and interest rates.

One of Eichholtz’s colleagues, Mathijs Korevaar, was so kind to provide me their data up till September 2021. In an email he wrote me that after 2019 prices have risen to such an extent that their model suggests real estate in Amsterdam is now overvalued. Below is the chart of Amsterdam real housing prices from 1620 through September 2021.

What happened in the 1990s that pushed housing prices far above prices during Holland’s Golden Age in the 17th century and second Golden Age in the late 19th century? To obtain a broader understanding of the housing market—beyond a model based on rent prices and interest rates—I read the work of an economist specialized in land, housing and banking: Josh Ryan-Collins.

The Mortgage Revolution

According to Ryan-Collins there have been two major developments in the housing market since the tun of the 19th century: a change in land tax and financial deregulation. Although he mostly researched Anglo-Saxon economies, I cross-checked his findings in the Netherlands.

Classic economists, such Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill, viewed land an asset incomparable to other assets, mainly because it’s in fixed supply and immobile. If demand for land increases, the price rises without triggering more supply. As a consequence, if there is economic growth, the value of land—on which houses are build—rises disproportional to goods and services (even if the owner of the land plays no role in the creation of that value). The solution of Smith and Mill was to tax land, more so than labour or profits. Indeed, in the 18th and 19th century land tax was a major source of income in the U.S. and Europe.

Then came the neoclassical economists that did away with the aforementioned theories on land. In the 20th century a shift emerged from land tax to income tax. It became increasingly more attractive to own a house as a financial asset. All that was missing was a way to finance real estate.

From the 1930s through 1970s the governments in most advanced economies imposed “credit guidance” on banks, which restricted mortgage lending. By preference banks lend mortgage credit over corporate credit, because the former is less risky. Commonly, the house bought with a mortgage serves as secure collateral for the loan. In case the borrower goes bankrupt, the bank can obtain the collateral and the damage is confined. In case of lending to a business, there can be no collateral or collateral of low quality. For society, though, lending to productive businesses is essential, as it creates sustainable economic growth and incomes to service debt. But credit guidance has slowly been dismantled, and as a result banks’ mortgage credit overtook non-mortgage credit in 1995. The mortgage revolution was a fact.

A bank creates money out of thin air when it lends credit. So, in case banks are lending mortgage credit the money supply is expanded, but the money is spend on a limited quantity of houses. The money supply is elastic, while the supply of houses is inelastic. No wonder that in the 1990s housing prices went up. Subsequently, the housing-finance feedback cycle was triggered: higher housing prices created more demand for mortgages, which further pumped up prices, resulting in more demand for mortgages, and so on.

The securitization of mortgages, that took off in the 1990s, also contributed to “the cycle.” Securitization enables banks to bundle and package mortgages into a Mortgage Backed Security (MBS). An illiquid asset (mortgage) is turned into a liquid asset (MBS) that can be sold, for example, to a pension fund. Banks earn fees for selling MBSs, and when the securities are off their balance sheet, it leaves more room for new mortgage lending.

Last but not least, the capital controls that were lifted after the breakdown of Bretton Woods in 1971, meant that banks were no longer dependent on domestic deposits for their funding. Banks gained access to international money markets, where they could attract additional funding for housing credit.

Escalating property prices result in a higher house price-to-income ratio and thus less consumer spending. This loss in spending in the housing-finance feedback economy is compensated by the “wealth” generated from increased housing prices. People that have unrealized gains on their property will, i.e., spend more because they feel wealthier (wealth effect), or take out a second mortgage to buy a boat (equity withdraw). Other people’s profits increase through speculating on real estate. But consumption can only keep up for as long as the cycle is perpetuated.

Conclusion

The cycle needs more debt and increasing housing prices. This unsustainable debt spiral endures by the grace of central banks lowering interest rates. In my view, the above resembles a ponzi scheme and the housing market is in a bubble. Although I am not certain how long this situation will last and how the bubble will pop. Perhaps nominal housing prices will decline, perhaps inflation will rise such that real housing prices retrace their long-term average. A problem with declining nominal prices is that it can tear down the banking system, something central banks want to prevent, as banks have massive exposure to mortgages.

I would like to stress that not every (advanced) economy has the same housing market. Neither do mortgage debt levels rise in a linear fashion. After the Great Financial Crisis in 2008 housing prices and mortgage debt levels fell in many economies. In response to the crisis governments came to the rescue to bail out banks and support the economy—which increased government debt. The housing bubble was not allowed to fully deflate. Interest rates hit zero, real interest rates went negative, and the cycle was re-activated. Housing prices resumed their ascent.

Furthermore, an academic paper (“More Mortgages, Lower Growth?”) from 2016 by Dirk Bezemer et al states:

In newly collected data on 46 economies over 1990-2011, we show that financial development since 1990 was mostly due to growth in credit to real estate and other asset markets, which has a negative growth coefficient. … We find positive growth effects for credit flows to nonfinancial business but not for mortgage and other asset market credit flows. …

Not only did the mortgage revolution “crowd out” credit for productive businesses, the credit flow to mortgages has a negative growth effect.

Can it be that the mortgage revolution, which has stifled growth, combined with a fiat international monetary system that enables unlimited debt levels, has spawned the greatest debt trap in the history of the world?

Finally, in the Netherlands, and I suppose elsewhere, the most mentioned solution for unaffordable housing is to simply build more houses. This approach fails, because banks can always print money faster than anyone can build houses. The solution is to be found on the demand side, not the supply side.

If you enjoyed reading this article please consider to support The Gold Observer and subscribe to the newsletter.

Sources

Belasting & Douane Museum. Digitale reis door de geschiedenis van belastingen in Nederland

Bezemer, D. 2014. Schumpeter Might Be Right Again: The Functional Differentiation of Credit.

Bezemer, D., Grydaki, M., and Zhang, L. 2016. More Mortgages, Lower Growth?

Bezemer, D., Samarina, A., and Zhang, L. 2017. The Shift in Bank Credit Allocation: New Data and New Findings.

Eichholtz, P. 1997. A Long Run House Price Index: The Herengracht Index, 1628-1973.

Eichholtz, P., Ambrose, B, and Lindenthal, T. 2012. House Prices and Fundamentals: 355 Years of Evidence.

Ferguson, N. 2008. The Ascent of Money.

Harari, Y.N. 2018. Money.

Jordà, Ò., Schularick, M., and Taylor, A.M. 2014. The Great Mortgaging: Housing Finance, Crises, and Business Cycles.

Korevaar, M., Eichholtz, P., and Francke, M. 2021. Dure Huizen Maar Geen Zeepbel in Amsterdam.

Monsma, J.A., Monsma, A.P. Is een Ingrijpende Herziening van het Gemeentelijke Belastinggebied Opportuun?

Park, H.Y., Chang, H., Misra, K. 2012. The Impact of Mortgage Securitization on Housing bubble and Subprime Mortgage Crisis: A Self-organization Perspective.

Riel, A. van. 2016. Het Financieel Stelsel in Historisch Perspectief.

Ryan-Collins, J., Werner, R., Jackson, A., and Greenham, T. 2012. Where Does Money Come From?

Ryan-Collins, J. 2019. Why Can’t You Afford a Home?

Jan, as per usual quality analysis.

One point of constructive criticism though.

From your conclusion, "Finally, in the Netherlands, and I suppose elsewhere, the most mentioned solution for unaffordable housing is to simply build more houses. This approach fails, because banks can always print money faster than anyone can build houses. The solution is to be found on the demand side, not the supply side.

I agree what you are saying here, but I think any solution is neither about demand or supply. Instead, I would suggest a solution is of a legal nature.

As you write, banks are able to create credit on the basis of their own balance sheet -- which in itself is not restricted by any deposits or other external funding (and so banks create credit 'out of nothing') -- yet the key understanding this accounting process is that banks always need a borrowers balance sheet to take collateral from. The question for banks is always about the collateral of borrowers.

Now, if you ask me, high bubbly prices are a consequence of <<future income>> having become the collateral basis for extending credit. This is what changed during the 90s.

When banks extend credit with houses as collateral, what happens when a mortgagee defaults? The house is sold and the mortgagee's debt is cancelled. Consequently, all financial risk are contractually borne by both debtor and creditor. Especially because banks will insist mortgagees put personal equity in the mortgaged house so that this equity functions as a buffer for banks to limit losses. (See Luigi Zingales Plan B for more how exactly so). Banks then are naturally inclined to refrain from over-crediting because at some point, they create future losses.

Plus another big benefit would be that all private contracts of credit, necessarily become self-liquidating by means of legal stipulation. Instead, they are shifted off to unrelated third parties, be it taxpayers due TBTF, not-so-savvy buyers of securitizations (pension funds and alike), or central banks printing ad infinitum to prop up markets.

What we have now in the Netherlands and elsewhere is very different because when mortgagees default, their houses gets auctioned off ('how many cents on the dollar..?') and the residual losses are entirely borne by mortgagees. Why? Their income has been taken as collateral. The house and its price, under this legal regime has always been beside the point when banks extend credit.

Because banks do not face a legal obligation of mutual risk-bearing, naturally, they maximize their profits by over-crediting, because "see, house prices can only rise", right?

...and you won't hear any Lawmaker complain about this in public, because this very same principle of collataralizing future income is exactly how they (mis)manage our public finances...

Excellent. Why not be more transparent? Good point. It helps quash the doubters which is important.