What Went Wrong In 1971

An interview with the gentlemen behind the website "WTF Happened in 1971?"

Written by Jan Nieuwenhuijs, originally published at Voima Gold Insight.

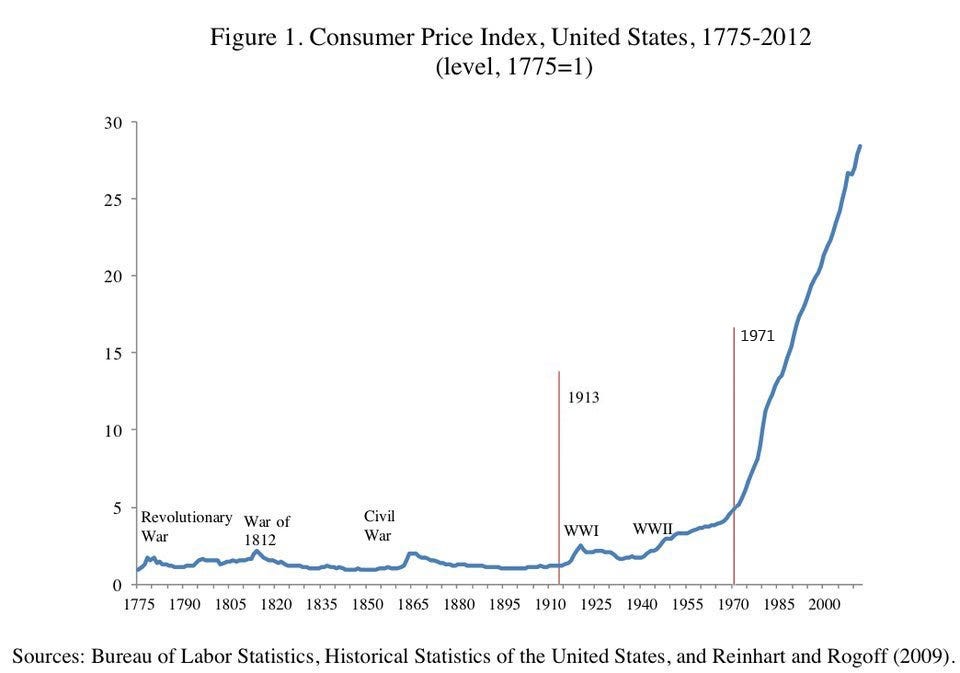

The last remnants of the gold standard were abandoned in August 1971, when President of the United States Richard Nixon decided to close the gold window (foreigners couldn’t redeem dollars for gold at the Treasury anymore). From 1945 until 1971, the U.S. dollar was backed by gold, and served as the world reserve currency under a system called Bretton Woods.

The “Nixon Shock”—as the unilateral suspension of Bretton Woods is often referred to—brought about a sea of change in economies and societies around the world, because from that moment on all national currencies stopped having an anchor. Fiat currencies could be created boundlessly. To get an understanding of the changes since 1971, I decided to interview the gentlemen behind the website “WTF Happened in 1971?”

If you don’t know this website, make sure to have a look. On the homepage you will find a collection of charts that all show a remarkable change around 1971. The founders of the website are Ben and Collin from the U.S., and I truly enjoyed talking to them. (Most of the charts in this article are sourced from their website.)

Jan: So, who are you guys? What is your background?

Ben: My background is very diverse. I have lots of interests, lots of hobbies. I have 3D graphics background. I don't have an economics background, but as of recently I got very interested in economics. I'm the type of person that when I get into something, I tend to go all the way and learn as much as possible. We obviously found this rabbit hole and most of it's from our study of money and monetary economics.

Jan: How did your interest in economics begin?

Ben: I got interested in it, because I got interested in bitcoin, and I tried to understand bitcoin, but realized I didn't understand what money was. And that required asking a lot of questions about the history of money, how it emerged, and what its purpose is in society.

Jan: Same questions for you Collin.

Collin: So, we're both amateur Austrian economists. That would probably be how we define ourselves. Neither of us have any formal education in finance, or business, or economics, which in a lot of ways has actually been to our benefit. We just like to ask questions, and we—as we continued to ask questions—identified what we think are the first principles of economics. We realized that that's the best way for people to learn, by asking questions first rather than starting with a conclusion.

Jan: What made you launch the website about economic developments that started in1971?

Ben: Through learning about the history of money, we discovered the Nixon Shock and the ending of the Bretton Woods agreement. If you look at the Wikipedia page, for example, on the Nixon Shock, you’ll see a few of the charts that are on our website. I thought these charts are fascinating, they show an important fundamental change in our society. It had along with it some interesting data that exploded in that time [1971], and we started collecting more and more of these charts. We wished we had a repository where we could just put all these charts to point people to. And the meme was born. It was Collin's idea to just ask the question: what the f*ck happened in 1971?

Jan: What do you say are the most significant developments that have occurred since 1971.

Collin: Monetary expansion—but we get a lot of criticism on this. People say, “oh you're not taking into account many of the regulatory changes, or the socio-cultural changes that happened around that same time period, that caused some of these second and third order effects that you attribute to this one 1971 data point.” If you were to sit down and talk with us, we'd tell you that the story goes back much further. We would trace it back to 1944 and 1933, and we would look at the Great Depression in America in 1929. We'd look at the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913, and then ideally, we'd go all the way back to the birth of fiat currencies in the United States before the U.S. was even a country. We'd look at the early fiat experiments, we'd go back to the bi-metal standards, we'd look at the process of coin clipping under the feudal lords. The story obviously doesn't start in 1971, but certainly that's when there's an interesting inflection in the data that you can point to and say: “look what happened here, everything went crazy.”

We attribute the expansion of monetary policy to gross malinvestment. Malinvestment that's perpetuated and unable to be liquidated, in such a way that it creates second and third order problems in our society that are exacerbated as this bubble continues to be expanded, and the can of the liquidation of malinvestment is kicked down the road.

Jan: On your website, the first chart I see is about inequality. How does what you just said ties into inequality in society?

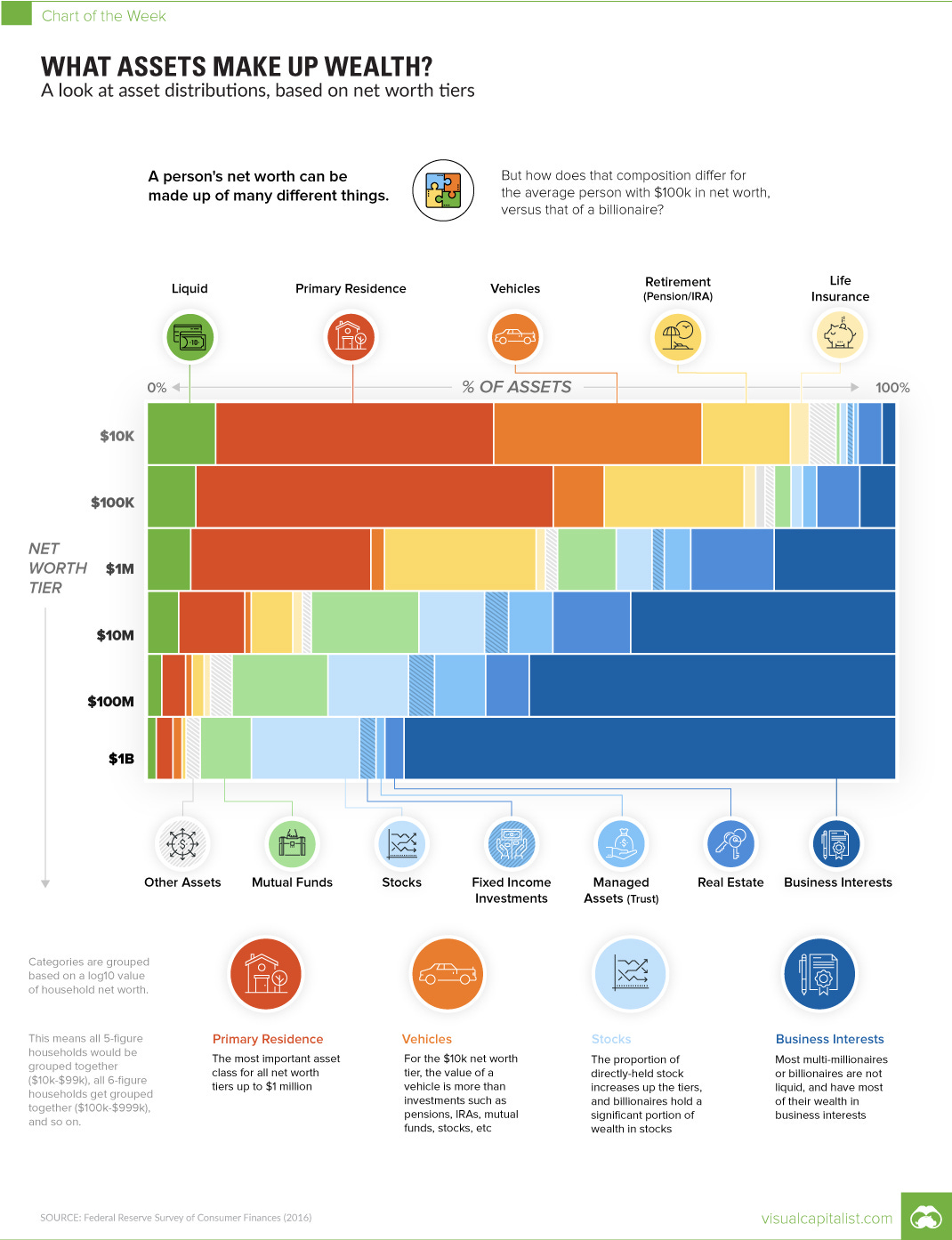

Ben: I think the greatest driver of inequality today is financial asset inflation, which is a direct result of monetary expansion. When you increase the money supply, you're going to increase the costs of hard supplied assets like stocks for example. And the deterioration of the moneyness of money—because the store of value aspect of money is important—has led society to use financial assets as money, like stocks and real estate. Many people hold their wealth in financial assets and every financial advisor will tell you, “don't hold dollars as a store of value.” So, the disproportionate access to financial assets, causes a wealth stratification in society, because the poorer you are the less access you have to financial assets as a percentage of your wealth, and the more wealthy you are, the larger percent of your wealth you hold in financial assets.

I have a chart that shows at different wealth levels a car is what percentage of your wealth. For people having a low income, their car makes up a significant share of their assets.

But a car is a depreciating asset. However, the wealthy hold 95 percent of their wealth in financial assets that inflate because of monetary expansion, and their car constitutes only a tiny part of their wealth. Stocks are very disproportionately held by the wealthiest. Something like 10 percent of the population holds 84 percent of all stocks. These dynamics have drawn society apart and hollowed out the middle class.

Jan: At the moment there’s a lot of social unrest in the United States. Do you think this is related to that the topic we’re discussing?

Ben: Yes.

Collin: People don't internalize why, but they look around and they understand that things are wrong. They understand that intuitively. Being of our generation [millennial], or even the younger that enter the world, that have no exposure to the “financial asset inflation ponzi,” they're starting off their lives at a disadvantage.

It's much harder for them to get an education, it's much harder for them to get assets that appreciate by inflation such as a home or stocks, and then they're working with a depreciating currency to store their value in the short term, in order to build a base for themselves.

And to add on to what Ben said. What we've also seen is a major disruption in economic calculation, because of the artificially low discount [interest] rate that we've seen for so long that's perpetuated by central banks since the late 1980s in the United States. We've seen the discount rate continue to be artificially pushed down, despite the fact that there isn't the accumulation of capital that in a free market would normally push that discount rate towards lower numbers. We're seeing that number artificially brought down by central banks.

You're watching the replacement cost of assets exceed the replacement cost of capital. Capital is so cheap for some businesses, that they are more financially incentivized to borrow money, and use that money to pump the price of their stocks rather than reinvest and serving the demands of the consumer. And this is why we see companies in America like Apple, which are very cash rich, borrowing money in order to buy back their stocks, so that they can pump the value of their assets rather than try to earn capital by being entrepreneurs, which is how the world is supposed to work in a free market.

Jan: At the moment, it seems to me that the only thing that is keeping the economy going is the next bubble. Would you agree?

Collin: Yes. It's a feedback loop of pumping liquidity into the system to prevent the liquidation of malinvestment. But as that liquidity enters the system more malinvestment is created and the bubble just gets bigger.

Ben: This is the idea of zombie companies and the zombie economy I’m sure you’re familiar with. Those are the malinvestment companies that should have probably gone under, weren't it for zero percent interest loans that keep them alive, and them still staying around. It’s destructive to society because these things should have been liquidated.

Collin: If you study the business cycle, you'll see that these things are very predictable. They tend to go in 10-year cycles. Currently, everyone is attributing our current economic downturn to the coronavirus pandemic, and is saying, “no one could have seen the corona crisis coming.” While, if you were paying close attention to financial markets in the precursor of corona, you were seeing warning signs that things were beginning to malfunction.

You were watching the repurchase agreement [repo] markets meltdown in the United States. Financial institutions were choosing interest on excess reserves at the Fed over participation in the repo market, which doesn't make sense in a market where there's profit to be made. Those are warning signs. You saw an inversion of the yield curve in the Treasuries market, and an extremely low unemployment rate. These are warning signs, by the Fed's own admission of a potential upcoming recession in 12 to 18 months. And yet, because of the public's lack of awareness to these economic principles, they think that this economic downturn was caused solely by governments and corporate organizations demanding that people stay home and don't work. Rather than it being attributed to the business cycles that always happen under these types of expansionary monetary policies.

Jan: Do you think there's a strong lobby from the banking industry to keep this system how it is? Because, for example, we can also point to deregulation that has caused problems, but maybe this was lobbied by special interest groups, which was possible because since 1971 we don't have an anchor to gold anymore.

Ben: That's it. I actually think this is one of the greatest misconceptions about the data on our site. There's a version of our website that does exactly the same thing as we do, but they point to 1980, Ronald Reagan, and deregulation as the cause. And I find that so fascinating. This is the opposite of what I believe. I believe deregulation would be a good thing if we have hard money. But it's because of the soft money that deregulation causes problems—not the deregulation itself.

Jan: So, the cause is central banks’ monetary expansion?

Collin: We often attribute central banks to the feudal lords that clipped the coins and then recirculated the currency at their face value. If you study things like the Cantillon effect, you know that those with the fewest degrees of separation from the printing press benefit the most from the creation of new currency. And that's by design, it has to work that way. If you were to increase the nominal currency values of everybody at the same time equally across the board, nothing would change. In expansionary monetary policies the relative purchasing power of certain groups are affected more than others, or else you are not redistributing wealth, and expansionary monetary policy effectively does nothing.

Jan: The answer is that without central banks we would be better off?

Collin: Absolutely.

The recording of this interview was not meant to be published, but as Ben and Collin were very pleased with the conversation, I sent them the audio, which they have published as a podcast. If you would like to listen to more of this conversation, please click here.